Overview

This report explores how people living in the Netherlands use supermarket apps and investigates how app usage compares and translates to the in-store supermarket experience.

For the purpose of this investigation, both the Jumbo App and Albert Heijn's "Appie" app were evaluated.

My role: I was the principal researcher and conducted this research project independently in fulfillment for a course in "Field Research Methods" during my MSc. in Interaction Design program.

Online supermarket shopping has emerged as a modern and convenient way to restock household groceries without dealing with the hassle and effort of having to leave one’s home. However, due to the Covid-19 pandemic, online grocery shopping for many has become the only safe and viable option to access food and offerings from the supermarket.

The purpose of this study was to examine and qualitatively determine how people in the Netherlands make use of and interact with Dutch supermarket apps to facilitate their household grocery shopping.

The study also aims to explore how the apps, in terms of features and design elements, emulates or differs from the in-store shopping experience.

Overview

This report explores how people living in the Netherlands use supermarket apps and investigates how app usage compares and translates to the in-store supermarket experience.

For the purpose of this investigation, both the Jumbo App and Albert Heijn's "Appie" app were evaluated.

My role: I was the principal researcher and conducted this research project independently in fulfillment for a course in "Field Research Methods" during my MSc. in Interaction Design program.

Online supermarket shopping has emerged as a modern and convenient way to restock household groceries without dealing with the hassle and effort of having to leave one’s home. However, due to the Covid-19 pandemic, online grocery shopping for many has become the only safe and viable option to access food and offerings from the supermarket.

The purpose of this study was to examine and qualitatively determine how people in the Netherlands make use of and interact with Dutch supermarket apps to facilitate their household grocery shopping.

The study also aims to explore how the apps, in terms of features and design elements, emulates or differs from the in-store shopping experience.

Process

This study was conducted in the Netherlands and included participants of whom were residents of the Netherlands, both Dutch and non-Dutch citizens. The study took place in the context of participant homes as well as the home of the principal researcher. Due to the limitations of in- person contact, due to the Covid-19 pandemic regulations and time constraints, the study could not be conducted as widely as desired among many diverse participants.

Research questions

RQ1: How do people use grocery shopping and delivery apps during a pandemic?

RQ2: How does this process compare to one’s in-store shopping experience?

Process

This study was conducted in the Netherlands and included participants of whom were residents of the Netherlands, both Dutch and non-Dutch citizens.

The study took place in the context of participant homes as well as the home of the principal researcher. Due to the limitations of in- person contact, due to the Covid-19 pandemic regulations and time constraints, the study could not be conducted as widely as desired among many diverse participants.

Research questions

RQ1: How do people use grocery shopping and delivery apps during a pandemic?

RQ2: How does this process compare to one’s in-store shopping experience?

Methodology

Mobile apps from both Jumbo and Albert Heijn, the two most successful supermarkets in the Netherlands, were used [6].Both apps are the most widely utilized by people in the Netherlands for online grocery shopping in comparison with other supermarket apps.

Participant recruitment: Four participants in total were gathered via convenience sampling. Inclusion criteria were the ownership and regular use of a smart phone (e.g., iPhone, Samsung, Android, etc.). Individuals who have, and have not, used the Jumbo and/or Supermarket app were also eligible to participate.

Participants were selected from an existing network of family members, neighbors, and friends. Participants were informed that participation was entirely voluntary, they could stop at any time, and that all results were anonymous and confidential.

The demographic breakdown was as follows: P1 (male, 37 years old, lives with partner and two children, P2 (female, 33 years old, lives with husband and two children), P3 (female, 59 years old, lives with husband), and P4 (male, 62 years old, lives with wife).

All participants included in the study...

- Lived in the Randstad region of the Netherlands

- Lived either in North and South Holland

- Lived in mid-sized villages (between 5-10 thousand residents)

- Were home-owners

- Had two or more children

- Had previously used (or currently use) the Jumbo and/or Albert Heijn app

*For the sake of a better representative sample, it would have been ideal to recruit participants in a more random manner whereby the participants had no former association or familiarity with the researcher. However, due to the time limitations of the study, it was more practical to select individuals of whom rapport was already established.

Methodology

Mobile apps from both Jumbo and Albert Heijn, the two most successful supermarkets in the Netherlands, were used [6].

Both apps are the most widely utilized by people in the Netherlands for online grocery shopping in comparison with other supermarket apps.

Participant recruitment: Four participants in total were gathered via convenience sampling. Inclusion criteria were the ownership and regular use of a smart phone (e.g., iPhone, Samsung, Android, etc.). Individuals who have, and have not, used the Jumbo and/or Supermarket app were also eligible to participate.

Participants were selected from an existing network of family members, neighbors, and friends. Participants were informed that participation was entirely voluntary, they could stop at any time, and that all results were anonymous and confidential.

The demographic breakdown was as follows: P1 (male, 37 years old, lives with partner and two children, P2 (female, 33 years old, lives with husband and two children), P3 (female, 59 years old, lives with husband), and P4 (male, 62 years old, lives with wife).

All participants included in the study...

- Lived in the Randstad region of the Netherlands

- Lived either in North and South Holland

- Lived in mid-sized villages (between 5-10 thousand residents)

- Were home-owners

- Had two or more children

- Had previously used (or currently use) the Jumbo and/or Albert Heijn app

*For the sake of a better representative sample, it would have been ideal to recruit participants in a more random manner whereby the participants had no former association or familiarity with the researcher. However, due to the time limitations of the study, it was more practical to select individuals of whom rapport was already established.

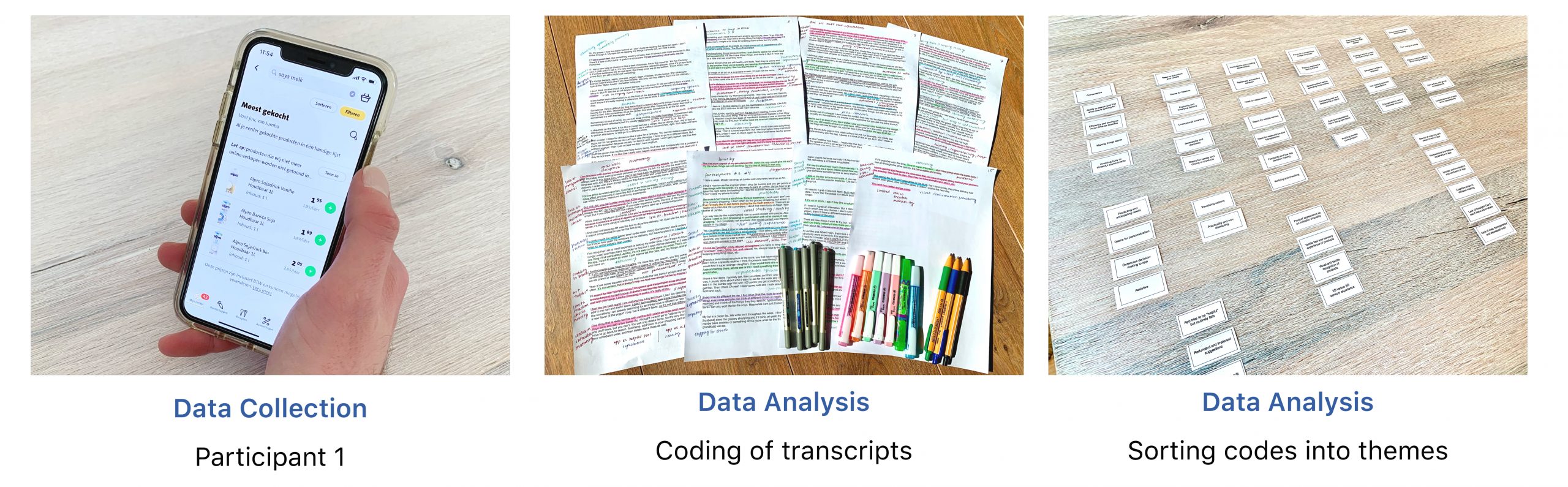

Data Collection

Step 1

Semistructured interviews using the contextual laddering method were conducted in order to identify and elaborate on the attributes, consequences, and values of participants within the grocery shopping experience, both in-app and in-person at the physical grocery stores. This method is a powerful way to understand people’s core values and beliefs [3].

Step 2

The interview protocols were prepared both in English and in Dutch and the interviews lasted one-hour each, on average. Interviews were recorded using the “Voice Memos” app on an iPhone XS and participants gave verbal consent to be recorded during the interviews. Participants occasionally opened the Jumbo and/or Albert Heijn app on their phones as a means of reference to show and explain their opinions and feedback when prompted about app-related questions.

Step 3

Participants were observed in situ while they used either the Albert Heijn or Jumbo app to place their weekly grocery delivery order. This was done in an informal, unstructured way where participants had freedom as to how they would interact with the app. The Concurrent Think-Aloud (CTA) method was used where participants verbalized their thoughts and interactions with the app aloud. Having this in-person experience was extremely valuable to better understand participants’ thoughts, elicit real-time feedback and emotional responses [4, 5].

Additional Notes

Participants generally felt relaxed while using the app and interacting during the research process since all participants in the sample were very familiar with using the supermarket apps and rapport was already established.

Participants gave consent to be video recorded using an iPhone. Notes were taken during observation. As a token of appreciation for their efforts, participants were sent a bouquet of spring flowers with a “Thank You” note after taking part in the study.

Data Collection

Step 1

Semistructured interviews using the contextual laddering method were conducted in order to identify and elaborate on the attributes, consequences, and values of participants within the grocery shopping experience, both in-app and in-person at the physical grocery stores. This method is a powerful way to understand people’s core values and beliefs [3].

Step 2

The interview protocols were prepared both in English and in Dutch and the interviews lasted one-hour each, on average. Interviews were recorded using the “Voice Memos” app on an iPhone XS and participants gave verbal consent to be recorded during the interviews. Participants occasionally opened the Jumbo and/or Albert Heijn app on their phones as a means of reference to show and explain their opinions and feedback when prompted about app-related questions.

Step 3

Participants were observed in situ while they used either the Albert Heijn or Jumbo app to place their weekly grocery delivery order. This was done in an informal, unstructured way where participants had freedom as to how they would interact with the app.

The Concurrent Think-Aloud (CTA) method was used where participants verbalized their thoughts and interactions with the app aloud. Having this in-person experience was extremely valuable to better understand participants’ thoughts, elicit real-time feedback and emotional responses [4, 5].

Additional Notes

Participants generally felt relaxed while using the app and interacting during the research process since all participants in the sample were very familiar with using the supermarket apps and rapport was already established.

Participants gave consent to be video recorded using an iPhone. Notes were taken during observation. As a token of appreciation for their efforts, participants were sent a bouquet of spring flowers with a “Thank You” note after taking part in the study.

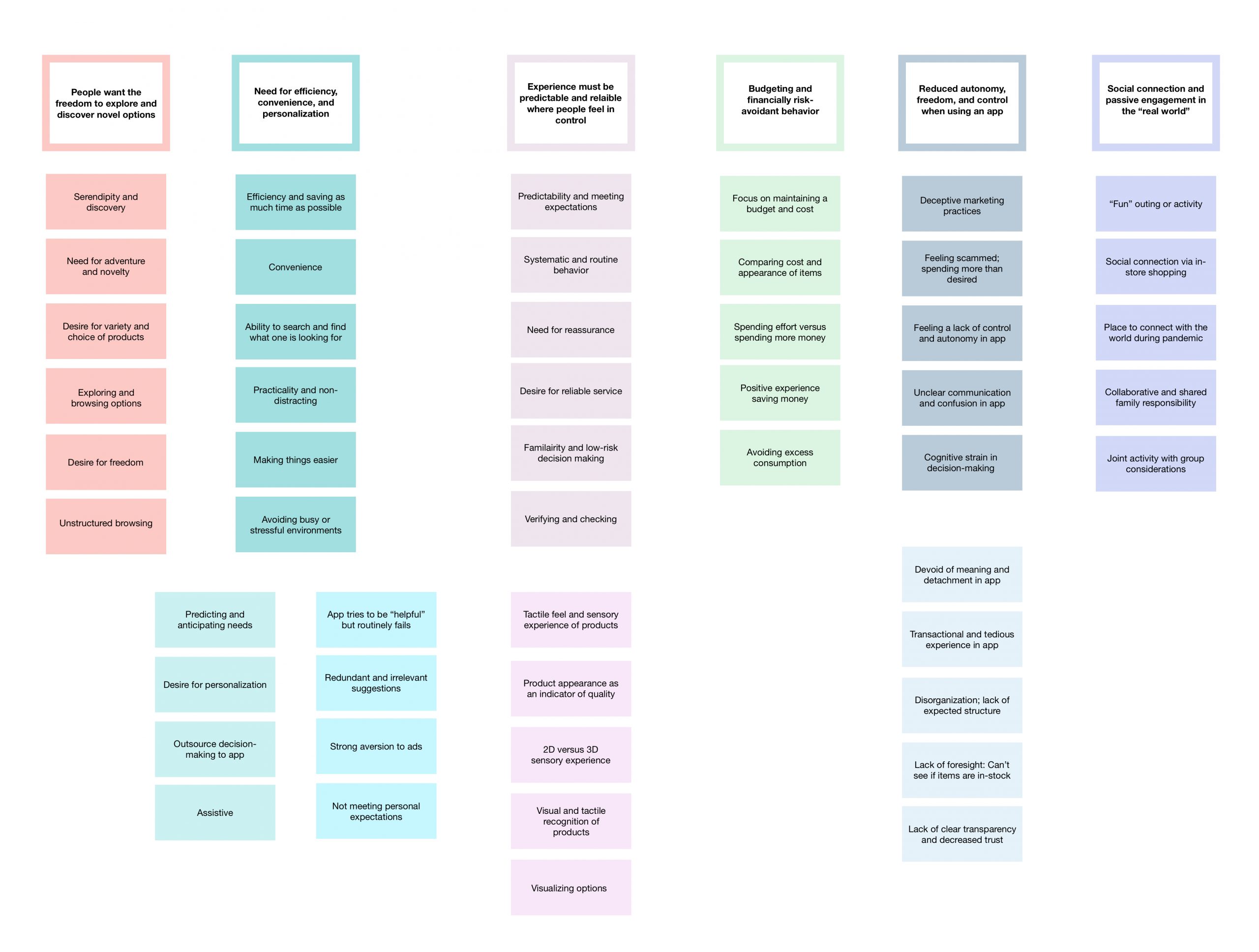

Data Analysis

Step 4

All recorded data, from both the initial contextual laddering interview and the CTA sessions, were transcribed verbatim, translated from Dutch to English where necessary, and coded using an inductive thematic analysis.

The process of inductive thematic analysis involves six phases (1) familiarization with the data, (2) generation of codes, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and naming categories, and (6) producing a final report [2, 7]. Coding was done without preconceived notions of what the categories might be [1].

Whether a code was “relevant” was based on salient findings in the text data that were recurrent, had a strong emotional component, significant, or otherwise “jumped out” as important.

Coding was done by hand annotating transcripts Codes were then made into digital, rectangular “sticky notes” using Sketch app, these notes were printed, cut out, and sorted by hand on a table. After, emergent themes were created on the basis of their “essence” and how well they related to answering the overall research questions and generated based on grouping codes by similarity. These themes were created and organized digitally using Sketch.

Data Analysis

Step 4

All recorded data, from both the initial contextual laddering interview and the CTA sessions, were transcribed verbatim, translated from Dutch to English where necessary, and coded using an inductive thematic analysis.

The process of inductive thematic analysis involves six phases (1) familiarization with the data, (2) generation of codes, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and naming categories, and (6) producing a final report [2, 7]. Coding was done without preconceived notions of what the categories might be [1].

Whether a code was “relevant” was based on salient findings in the text data that were recurrent, had a strong emotional component, significant, or otherwise “jumped out” as important.

Coding was done by hand annotating transcripts Codes were then made into digital, rectangular “sticky notes” using Sketch app, these notes were printed, cut out, and sorted by hand on a table. After, emergent themes were created on the basis of their “essence” and how well they related to answering the overall research questions and generated based on grouping codes by similarity. These themes were created and organized digitally using Sketch.

Results

The most important findings that emerged from this research were the following:

People valued the freedom to explore and discover novel options in terms of product choice and appreciated serendipitous experiences

The in-store supermarket experience allows for unstructured browsing and freedom of movement throughout the physical space to “stumble upon” new items which may interest them. All participants, whether or not they shopped primarily online or in-store, emphasized via their responses that they appreciated a sense of “adventure” in trying new supermarket products.

P1 remarked, “I feel like I already know all the fruits and vegetables, I’ve seen them all... But a snack would be something I’d try. I find diversity of flavors interesting, different flavors, different textures, like crunchy.” P2 stated, “Sometimes I’ll see an item in the store and it will jog my memory. If I see a new item, like protein bars, and I see they have a new flavor, I’d try it out.” P3 said, “Every time it’s different for me [going to the store]. I find it fun because you see different things every time and you can think of different dishes or meals.”

Results

The most important findings that emerged from this research were the following:

People valued the freedom to explore and discover novel options in terms of product choice and appreciated serendipitous experiences

The in-store supermarket experience allows for unstructured browsing and freedom of movement throughout the physical space to “stumble upon” new items which may interest them. All participants, whether or not they shopped primarily online or in-store, emphasized via their responses that they appreciated a sense of “adventure” in trying new supermarket products.

P1 remarked, “I feel like I already know all the fruits and vegetables, I’ve seen them all... But a snack would be something I’d try. I find diversity of flavors interesting, different flavors, different textures, like crunchy.” P2 stated, “Sometimes I’ll see an item in the store and it will jog my memory. If I see a new item, like protein bars, and I see they have a new flavor, I’d try it out.” P3 said, “Every time it’s different for me [going to the store]. I find it fun because you see different things every time and you can think of different dishes or meals.”

When using the supermarket apps for shopping and delivery, people felt reduced autonomy and control in their experiences

Each participant expressed that they felt they were, at times, being a victim of deceptive marketing practices from the supermarket and they felt the app was restricting their ability to maximize exploration. There were many points of confusion or disorganization when using the app which left people feeling frustrated or that they couldn’t rely on or trust the app to achieve their goals.

P4 stated, “I think the promotions [in the app] are a bit of a scam. They trick you into buying things. But I only but what I need to buy.” P2 mentioned, “The problem with Jumbo is that the deliveries are inconsistently reliable, it’s always this ‘black box’ where you’re not sure if you’re going to get your groceries in time... With Albert Heijn, you can’t order more than €250 euros which I find ridiculous because their groceries are already so expensive.” P1 commented, “I find it very abstract. I have no idea if I am buying six or two bags of groceries. On the last screen [of the Jumbo app] it’s just text. It’s too much reading. I have to guess what I bought is fine."

When using the supermarket apps for shopping and delivery, people felt reduced autonomy and control in their experiences

Each participant expressed that they felt they were, at times, being a victim of deceptive marketing practices from the supermarket and they felt the app was restricting their ability to maximize exploration. There were many points of confusion or disorganization when using the app which left people feeling frustrated or that they couldn’t rely on or trust the app to achieve their goals.

P4 stated, “I think the promotions [in the app] are a bit of a scam. They trick you into buying things. But I only but what I need to buy.” P2 mentioned, “The problem with Jumbo is that the deliveries are inconsistently reliable, it’s always this ‘black box’ where you’re not sure if you’re going to get your groceries in time... With Albert Heijn, you can’t order more than €250 euros which I find ridiculous because their groceries are already so expensive.” P1 commented, “I find it very abstract. I have no idea if I am buying six or two bags of groceries. On the last screen [of the Jumbo app] it’s just text. It’s too much reading. I have to guess what I bought is fine."

There was a strong generational divide between how people used supermarket apps. However, all participants voiced they felt the app experience was tedious and wished the app was more “helpful” and intuitive

The younger participants (37 and 33 years old) expressed they wished the app was more “assistive” in being more personalized and predictive with product suggestions. They expressed negative emotions towards being presented with irrelevant product promotions. The older participants (59 and 62) primarily used the app as a digital brochure to scout out good deals and weekly product discounts. They did not order grocery delivery as often as the younger generation.

P1 stated, “I would rather go straight to ordering. I don’t need more ads in my life. The starting page [of Jumbo] os not exactly ads, I guess, but promotions. If the promotion were relevant maybe I’d be interested... but not like the items I am already buying and that I am aware of.” P2 mentioned, “I wish I could add a personal review to an item so I can mark it like ‘I really enjoyed this one’ and give it 5-stars or something and the one I hated never shows up again.” P5 remarked, “<annoyed tone> I don’t like using the app because it’s more time you have to spend sitting behind your phone in the evening.You have to plan, they may not have everything in stock”

There was a strong generational divide between how people used supermarket apps. However, all participants voiced they felt the app experience was tedious and wished the app was more “helpful” and intuitive

The younger participants (37 and 33 years old) expressed they wished the app was more “assistive” in being more personalized and predictive with product suggestions. They expressed negative emotions towards being presented with irrelevant product promotions. The older participants (59 and 62) primarily used the app as a digital brochure to scout out good deals and weekly product discounts. They did not order grocery delivery as often as the younger generation.

P1 stated, “I would rather go straight to ordering. I don’t need more ads in my life. The starting page [of Jumbo] os not exactly ads, I guess, but promotions. If the promotion were relevant maybe I’d be interested... but not like the items I am already buying and that I am aware of.” P2 mentioned, “I wish I could add a personal review to an item so I can mark it like ‘I really enjoyed this one’ and give it 5-stars or something and the one I hated never shows up again.” P5 remarked, “<annoyed tone> I don’t like using the app because it’s more time you have to spend sitting behind your phone in the evening.You have to plan, they may not have everything in stock”

The in store-shopping experience provides multi-faceted sensory and social benefits for people that are not translated or communicated to the supermarket app environment

For most participants, the supermarket was a “fun” outing or activity whereby they felt like they could connect with the world in some way. For many, the supermarket was the only context where they saw other people, aside from household members, in-person. All participants relied on tactical feel of products, physical 3D appearance of products, and visualizing and recognizing product options a significant benefit of in-store shopping, which the app did not offer.

P1 stated, “I feel like there is a distance between me and the things I am buying. Like it’s not real... I’m just pressing the ‘plus’ button and the money is not physical so it’s all like pretend money, with pretend groceries and then you have real groceries after.” P2 said, “Sure I’d like to go [to the store] more often because it’s nice to see people and check out different items and feel like you’re part of the world <laughter> It’s a big ‘adventure’ at the supermarket.” P3 remarked, “The social aspect is important to me with people in my village. <laughter> I know a lot of people.” P4 commented, “I look at the prices to compare and I really check the expiration date, I want the product with the later date so it says fresh longer.

The in store-shopping experience provides multi-faceted sensory and social benefits for people that are not translated or communicated to the supermarket app environment

For most participants, the supermarket was a “fun” outing or activity whereby they felt like they could connect with the world in some way. For many, the supermarket was the only context where they saw other people, aside from household members, in-person. All participants relied on tactical feel of products, physical 3D appearance of products, and visualizing and recognizing product options a significant benefit of in-store shopping, which the app did not offer.

P1 stated, “I feel like there is a distance between me and the things I am buying. Like it’s not real... I’m just pressing the ‘plus’ button and the money is not physical so it’s all like pretend money, with pretend groceries and then you have real groceries after.” P2 said, “Sure I’d like to go [to the store] more often because it’s nice to see people and check out different items and feel like you’re part of the world <laughter> It’s a big ‘adventure’ at the supermarket.” P3 remarked, “The social aspect is important to me with people in my village. <laughter> I know a lot of people.” P4 commented, “I look at the prices to compare and I really check the expiration date, I want the product with the later date so it says fresh longer.

Implications for the main research questions

Based on the above findings, there was a strong distinction between those who used the apps as medium for ordering and delivering groceries like an eCommerce store (younger generation) and those who used the apps as a digital brochure for browsing weekly discounts (older generation).

The younger generation (30-40 years old) felt as if they were being spammed with irrelevant ads and promotions when using both the Albert Heijn and Jumbo app. The older generation (60 years and older) tried to use the app as little as possible and preferred going to the physical store. There was an interesting contrast between people’s desire to be efficient, save time, and have things predictable, yet also have the freedom to explore new options, take risks, and have novel experiences.

A commonly reoccurring word used by all participants was “checking,” as in to verify something.

The in-store experience gave participants a greater feeling of control and freedom to “check” that the product they were getting was good quality and would not expire soon; compare the product to similar products nearby in terms of price and visual appeal; and scan and explore similar options nearby.

Both apps, Jumbo and Albert Heijn, did not make “checking” behavior, as one would do in the store, easy or possible.

Many participants felt that the app was restricting and limited their ability to browse in an enjoyable way. For example, when using the app, users are not shown relevant product suggestions based on their purchase history, they are not shown similar alternatives when viewing a product, and they cannot compare prices or features between similar products.

Implications for the main research questions

Based on the above findings, there was a strong distinction between those who used the apps as medium for ordering and delivering groceries like an eCommerce store (younger generation) and those who used the apps as a digital brochure for browsing weekly discounts (older generation).

The younger generation (30-40 years old) felt as if they were being spammed with irrelevant ads and promotions when using both the Albert Heijn and Jumbo app. The older generation (60 years and older) tried to use the app as little as possible and preferred going to the physical store. There was an interesting contrast between people’s desire to be efficient, save time, and have things predictable, yet also have the freedom to explore new options, take risks, and have novel experiences.

A commonly reoccurring word used by all participants was “checking,” as in to verify something.

The in-store experience gave participants a greater feeling of control and freedom to “check” that the product they were getting was good quality and would not expire soon; compare the product to similar products nearby in terms of price and visual appeal; and scan and explore similar options nearby.

Both apps, Jumbo and Albert Heijn, did not make “checking” behavior, as one would do in the store, easy or possible.

Many participants felt that the app was restricting and limited their ability to browse in an enjoyable way. For example, when using the app, users are not shown relevant product suggestions based on their purchase history, they are not shown similar alternatives when viewing a product, and they cannot compare prices or features between similar products.

References

[1] Bohn, C. (2012). Analyzing Verbal Protocols: Thinking Aloud During Reading in Cognitive and Educational Psychology. https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781526494306

[2] Braun, V. and Clarke, V. (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 93. https://10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

[3] Hawley, M. (2009, June 9). Laddering: A Research Interview Technique for Uncovering Core Values. UXmatters. https://www.uxmatters.com/mt/archives/2009/07/laddering-a-research- interview-technique-for-uncovering-core-values.php

[4] Johnson, J., & Finn, K. (2017). Designing user interfaces for an aging population: Towards universal design. Morgan Kaufmann.

[5] Mayhew, P., & Alhadreti, O. (2018). Are two pairs of eyes better than one? A comparison of concurrent think-aloud and co-participation methods in usability testing. Journal of Usability Studies, 13(4), 177-195. https://ueaeprints.uea.ac.uk/id/eprint/71985/1/Published_Version.pdf

[6] Merkelijkheid. (2020, August 19). Positionering supermarkten: Albert Heijn vs. Jumbo. https:// merkelijkheid.nl/positioneren/positionering-albert-heijn-jumbo

[7] Mortensen, D. (2020, June 5). How to Do a Thematic Analysis of User Interviews. The Interaction Design Foundation. https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/how-to-do-a-thematic- analysis-of-user-interviews

[8] Van Someren, M. W., Barnard, Y. F., & Sandberg, J. A. C. (1994). The think aloud method: a practical approach to modelling cognitive behaviour. London: AcademicPress. https://hdl.handle.net/ 11245/1.103289

References

[1] Bohn, C. (2012). Analyzing Verbal Protocols: Thinking Aloud During Reading in Cognitive and Educational Psychology. https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781526494306

[2] Braun, V. and Clarke, V. (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 93. https://10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

[3] Hawley, M. (2009, June 9). Laddering: A Research Interview Technique for Uncovering Core Values. UXmatters. https://www.uxmatters.com/mt/archives/2009/07/laddering-a-research- interview-technique-for-uncovering-core-values.php

[4] Johnson, J., & Finn, K. (2017). Designing user interfaces for an aging population: Towards universal design. Morgan Kaufmann.

[5] Mayhew, P., & Alhadreti, O. (2018). Are two pairs of eyes better than one? A comparison of concurrent think-aloud and co-participation methods in usability testing. Journal of Usability Studies, 13(4), 177-195. https://ueaeprints.uea.ac.uk/id/eprint/71985/1/Published_Version.pdf

[6] Merkelijkheid. (2020, August 19). Positionering supermarkten: Albert Heijn vs. Jumbo. https:// merkelijkheid.nl/positioneren/positionering-albert-heijn-jumbo

[7] Mortensen, D. (2020, June 5). How to Do a Thematic Analysis of User Interviews. The Interaction Design Foundation. https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/how-to-do-a-thematic- analysis-of-user-interviews

[8] Van Someren, M. W., Barnard, Y. F., & Sandberg, J. A. C. (1994). The think aloud method: a practical approach to modelling cognitive behaviour. London: AcademicPress. https://hdl.handle.net/ 11245/1.103289